Renewable energies can be a powerful source of growth and prosperity. But it must be accompanied by a regulation allowing all consumers to benefit.

Two years of an unprecedented energy crisis have not been enough. It has not been enough that inflation in Europe has exceeded double digits, driven, among others, by the escalation of electricity prices and their translation to the prices of so many other goods and services. It has not been enough that this has contributed to the rise in interest rates by the European Central Bank (ECB), exacerbating the loss of households’ disposable income, making corporate investments more expensive, and devaluing the financial assets on bank balance sheets. It has not been enough that the increase in energy costs has jeopardized the competitiveness of European industry and, with it, the survival of some companies and jobs.

None of this has been enough for the European Commission to react with what would have been the most effective anti-inflationary measure: a pro-competitive reform of electricity markets. Its proposal does not bring anything new to prevent the episodes we have experienced during these years from repeating themselves. Nor does it provide the necessary instruments to address the energy transition in an efficient and equitable manner, allowing consumers to benefit from the lower costs of renewable energies and encouraging electrification as the main way to decarbonize the economy.

To prevent gas prices from contaminating electricity markets during crises, the Commission empowers Member States to regulate electricity prices for households. However, it does not specify how the difference between the price in the wholesale electricity markets – which will continue to be affected by gas prices – and the regulated retail price will be paid. Past and recent experience does not bode well. Minister Rodrigo Rato adopted a similar measure in Spain that resulted in the Electricity Tariff Deficit, almost 30 billion euros that all electricity consumers continue to pay. Similarly, during these two years, Member States, depending on their asymmetrical fiscal capacities, have cushioned the impact of energy costs through public aid. But in both cases, it is the electricity consumers and taxpayers who have ultimately ended up paying.

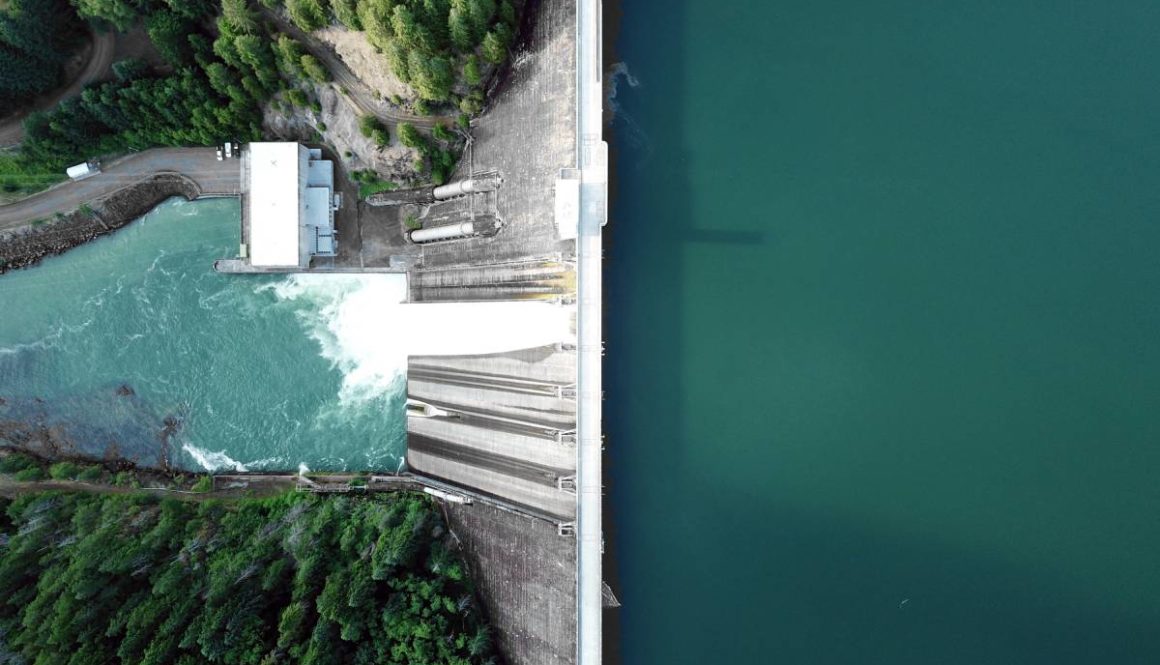

Regulating final prices does not avoid the problem because it does not tackle its root cause: the over-remuneration of some power generation plants (nuclear, hydroelectric, and renewables) when their production – with low costs, unrelated to gas fluctuations – is remunerated at prices that exceed three to ten times their own costs. Ursula von der Leyen had diagnosed this well in her State of the Union speech (“Low-carbon energy sources are earning enormous revenues they never dreamed of… [and which] do not reflect their production costs“) and so it is disappointing that the Commission’s proposal has ignored this indisputable reality. On the contrary, Member States should have been empowered to limit the remuneration of these plants, especially in cases where – as in Spain – these plants were installed before the implementation of the current electricity market, and for which the regulation always guaranteed the recovery of their costs, as has been indeed the case.

The Commission leaves industrial consumers unprotected, and recommends that they contract electricity at fixed prices to avoid volatility in their energy costs. But it forgets that the main problem is not volatility, but the price level. As it also forgets that it is not that the industry does not want to contract its electricity at stable and competitive prices, but that it is that it does not have the possibility to do so. There are not enough contracts with a long enough duration to cover the industry’s needs, and their prices are not competitive because they continue to reflect the prices of the short-term markets that inevitably are, under current regulation, their underlying reference.

The survival of the European industry depends on its energy costs being competitive. The best way to achieve this is not through subsidies but through an electricity market design that enhances competition. The current proposal offers little hope of mitigating the deindustrialization of Europe.

The Commission is right to preserve short-term markets to promote efficiency in electricity production. It is also right to denounce the lack of long-term contracting that should serve to encourage investment in renewables and the decoupling of electricity prices from gas prices. But it fails in the chosen mechanism: long-term bilateral private contracting between generators and large buyers (industrials or retailers). The Commission wants to encourage this type of contracting in three ways. On the one hand, it requires that Member States ensure the existence of sufficient contractual guarantees, which will require public aid. In addition to being costly for the public budgets, it could give rise to moral hazard problems. It also obliges electricity retailers to forward contract part of their sales, favoring integrated operators over independent operators, ultimately making the price of electricity more expensive for the end consumer. Finally, it proposes that the auctions held by the regulator should favor generators with these contracts, which would distort the efficient choice of renewable investments.

In any case, bilateral private forward contracting is not the solution. Besides being discriminatory against consumers with limited bargaining power -the vast majority-this type of contract does not solve customers’ coverage needs, and its opacity results in less competitive pressure and higher prices.

On the contrary, auctions of long-term contracts with the electricity system as counterparty -such as those held in Spain for investments in renewables- have proven to be effective in providing competitive and stable prices for the benefit of all consumers. Moreover, they give predictability to investments, a key issue for the industry to develop around the deployment of renewables. The Commission’s proposal should have required Member States to hold these auctions to cover a significant fraction of their investments committed through their national energy and climate plans. Not only has it failed to do so, but it recommends that these auctions be used as a last resort when the private bilateral contract market fails.

The electricity sector, hand in hand with the lower costs of renewable energies, can be a powerful source of economic growth and welfare. But it must be accompanied by an electricity regulation that ensures all consumers benefit from it. The choice of inappropriate regulatory instruments, such as those proposed by the Commission, could frustrate this. Just as it could frustrate the flourishing of a European industry around these investments or the avoidance of industry leakage. Finally, it is unacceptable for the Commission to allow electricity companies to benefit from “enormous revenues they never dreamed of” at the expense of European citizens and industry.

Now it is the turn of the European Parliament and the Council. It is their responsibility to redirect a disappointing proposal towards an electricity regulation that is up to the challenges.

Natalia Fabra

Professor of Economics, Carlos III University

This is a translated version of the Tribune published at EL PAIS on March 23, 2023

https://elpais.com/opinion/2023-03-23/europa-decepciona-en-la-cuestion-electrica.html

Europa decepciona en la cuestión eléctrica

De la mano de las energías renovables, el sector puede ser una fuente potente de crecimiento y bienestar. Pero tiene que ir acompañado por una regulación que asegure que todos los consumidores se beneficien de ello

Dos años de crisis energética sin precedentes no han sido suficientes. No ha sido suficiente que la inflación en Europa haya superado los dos dígitos, aupada, entre otros, por la escalada de los precios de la electricidad y su traslación a los precios de tantos otros bienes y servicios. No ha sido suficiente que ello haya contribuido a la subida de tipos de interés por parte del Banco Central Europeo (BCE), agudizando la pérdida de renta disponible de los hogares hipotecados, encareciendo las inversiones de las empresas y devaluando los activos financieros en los balances de la banca. No ha sido suficiente que el aumento de los costes energéticos haya puesto en riesgo la competitividad de la industria europea y, con ello, la supervivencia de algunas empresas y puestos de trabajo.

Nada de esto ha sido suficiente para que la Comisión Europea haya reaccionado con la que hubiera sido la medida antiinflacionista más eficaz: una reforma pro-competitiva de los mercados eléctricos. Su propuesta no aporta nada nuevo para evitar que los episodios que hemos vivido durante estos años se repitan. Como tampoco aporta los instrumentos necesarios para abordar la transición energética de forma eficiente y equitativa, permitiendo que los consumidores se beneficien de los menores costes de las energías renovables e incentivando la electrificación como vía principal para descarbonizar la economía.

Para evitar que en situaciones de crisis los precios del gas contaminen los mercados eléctricos, la Comisión habilita a los Estados miembro a regular los precios de la electricidad para los hogares. Sin embargo, no especifica cómo se va a pagar la diferencia entre el precio de los mercados eléctricos —que seguirá afectado por los precios del gas— y el precio regulado. La experiencia pasada y reciente no aporta buenos augurios. En España, el ministro Rodrigo Rato adoptó una medida similar que dio lugar al déficit tarifario, casi 30.000 millones de euros que todos los consumidores eléctricos seguimos pagando. De forma similar, durante estos dos años, los Estados miembro, en función de sus capacidades fiscales asimétricas, han amortiguado el impacto de los costes energéticos a través de ayudas públicas. Pero, en ambos casos, son los consumidores eléctricos y los contribuyentes los que, en última instancia, han acabado pagando.

Regular los precios finales no evita el problema porque no ataja su raíz: la sobrerretribución de algunas centrales de generación eléctrica (nuclear, hidroeléctrica y renovables) cuando su producción —de costes bajos, ajenos a las fluctuaciones del gas— es retribuida a precios que superan de tres a diez veces sus propios costes. Lo había diagnosticado bien Ursula von der Leyen en su discurso del Estado de la Unión (“Las fuentes de energía bajas en carbono están obteniendo ingresos con los que nunca soñaron… [y que] no reflejan sus costes de producción”) y por eso decepciona que la propuesta de la Comisión haya ignorado esa realidad incontestable. Por el contrario, se debía haber habilitado a los Estados miembro a limitar la retribución de estas centrales, máxime cuando en algunos casos —como en España— se trata de centrales previas a la implantación del mercado eléctrico vigente, y a las que la regulación siempre garantizó la recuperación de sus costes, como así ha sido.

La Comisión deja desprotegidos a los consumidores industriales, a quienes recomienda que contraten la electricidad a precios fijos para evitar la volatilidad en sus costes energéticos. Pero olvida que el principal problema no es la volatilidad, sino el nivel de precios. Como olvida también que no es que la industria no quiera contratar su electricidad a precios estables y competitivos, es que no tiene la posibilidad de hacerlo. No hay suficientes contratos a un plazo suficiente para cubrir las necesidades de la industria, y sus precios no son competitivos porque siguen reflejando los precios de los mercados de corto plazo que inevitablemente son, bajo la actual regulación, su referencia subyacente.

La supervivencia de la industria europea depende de que sus costes energéticos sean competitivos. La mejor manera de conseguirlo no es a través de subvenciones, sino a través de un diseño del mercado eléctrico que potencie la competencia. Bajo la propuesta actual, difícilmente se evitará la desindustrialización de Europa.

La Comisión acierta al preservar los mercados a corto plazo para promover la eficiencia en la producción eléctrica. También acierta al denunciar la falta de contratación a largo plazo que debería servir para fomentar las inversiones en renovables y el desacople de los precios de la electricidad de los del gas. Pero falla en el mecanismo elegido: la contratación bilateral privada a largo plazo entre generadores y grandes compradores (industriales o comercializadores). La Comisión quiere favorecer este tipo de contratos por tres vías. Por una parte, pide que existan garantías contractuales suficientes, lo que exigirá ayudas públicas que además de ser onerosas para las arcas públicas, podrían dar lugar a problemas de riesgo moral. También obliga a las comercializadoras de electricidad a contratar a plazo parte de sus ventas, favoreciendo a los operadores integrados frente a los comercializadores independientes, y encareciendo el precio de la electricidad para el consumidor final. Y, por último, propone que en las subastas que realice el regulador se favorezca a los generadores con energía contratada a plazo, lo que distorsionaría la elección eficiente de las inversiones en renovables.

En cualquier caso, la contratación bilateral privada a plazo no es la solución. Este tipo de mercados, además de ser discriminatorios con los consumidores sin capacidad de negociación —la inmensa mayoría—, no solucionan las necesidades de cobertura de los clientes, y su opacidad se traduce en una menor presión competitiva y mayores precios.

Por el contrario, las subastas de contratos a largo plazo con el sistema eléctrico como contraparte —como las celebradas en España para las inversiones en renovables— han demostrado ser eficaces para aportar precios competitivos y estables en beneficio de todos los consumidores. Además, dan predictibilidad a las inversiones, cuestión fundamental para que se desarrolle la industria en torno al despliegue de las renovables. La propuesta de la Comisión debía haber exigido a los Estados miembro celebrar estas subastas para cubrir una fracción significativa sus inversiones comprometidas en sus planes nacionales de energía y clima. Y no sólo no lo ha hecho, sino que recomienda que estas subastas se utilicen como un último recurso cuando el mercado de contratos bilaterales privados falle.

El sector eléctrico, de la mano de las energías renovables y de sus menores costes, puede ser una fuente potente de crecimiento económico y bienestar. Pero tiene que ir acompañado por una regulación eléctrica que asegure que todos los consumidores se beneficien de ello. La elección de instrumentos regulatorios inadecuados, como los que propone la Comisión, podría frustrarlo. Como también podría frustrar el que florezca una industria europea en torno a estas inversiones, o el que se evite la fuga de la industria. Por último, no es admisible que la Comisión consienta que la regulación eléctrica ampare rentabilidades con las que las empresas eléctricas “nunca soñaron”, a expensas de los ciudadanos y de la industria europea.

Ahora es el turno del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo. Reconducir una propuesta decepcionante hacia una regulación eléctrica a la altura de los retos es su responsabilidad.